DIE UNVERWELKLICHEN BLUMEN VON NILS DUNKEL by Norman Rosenthal

In this new age of radical puritanism is it possible, or even too luxurious for a young artist to aspire to new contemporary forms of “Romanticism”, that at one level seems so distant from what are thought to be the current realities of the world? But the nature of these realities are complex indeed, bound up with the crazy elusive truths buried in their epistemologies and their apparent opposites, the actual phenomenology of things.

However if dreams also have their own realities there is a sense that all that aspires to belong to the strange category of art, need have a consciousness of the subjective truths buried in the philosophies and literatures of the essential Romantic even if peppered sometimes, even often with a strong dose of irony. The quintessential German author of the subjective known commonly as Novalis and who conceived the “Blaue Blume” observes somewhere amongst his forth of his six “Hymnen an die Nacht” (1800) tells us:

“Trägt nicht alles, was uns begeistert, die Farbe die Nacht? Sie trägt dich mütterlich, und ihr verdankst du die deine Herrlichkeit. Du verflogst in dir selbst, in endlosen Räume zergingst du, wenn sie dich nicht hielte dich nicht bände, dass du warm würdest und flammend die Welt zeugtest. Wahrlich ich war, eh du warst – die Mutter schickte mit meinen Geschwistern mich, zu bewohnen deine Welt, sie zu heiligen mit Liebe, dass sie ein ewig angeschautes Denkmal werde – zu bepflanzen sie mit unverwelklichen Blumen.”

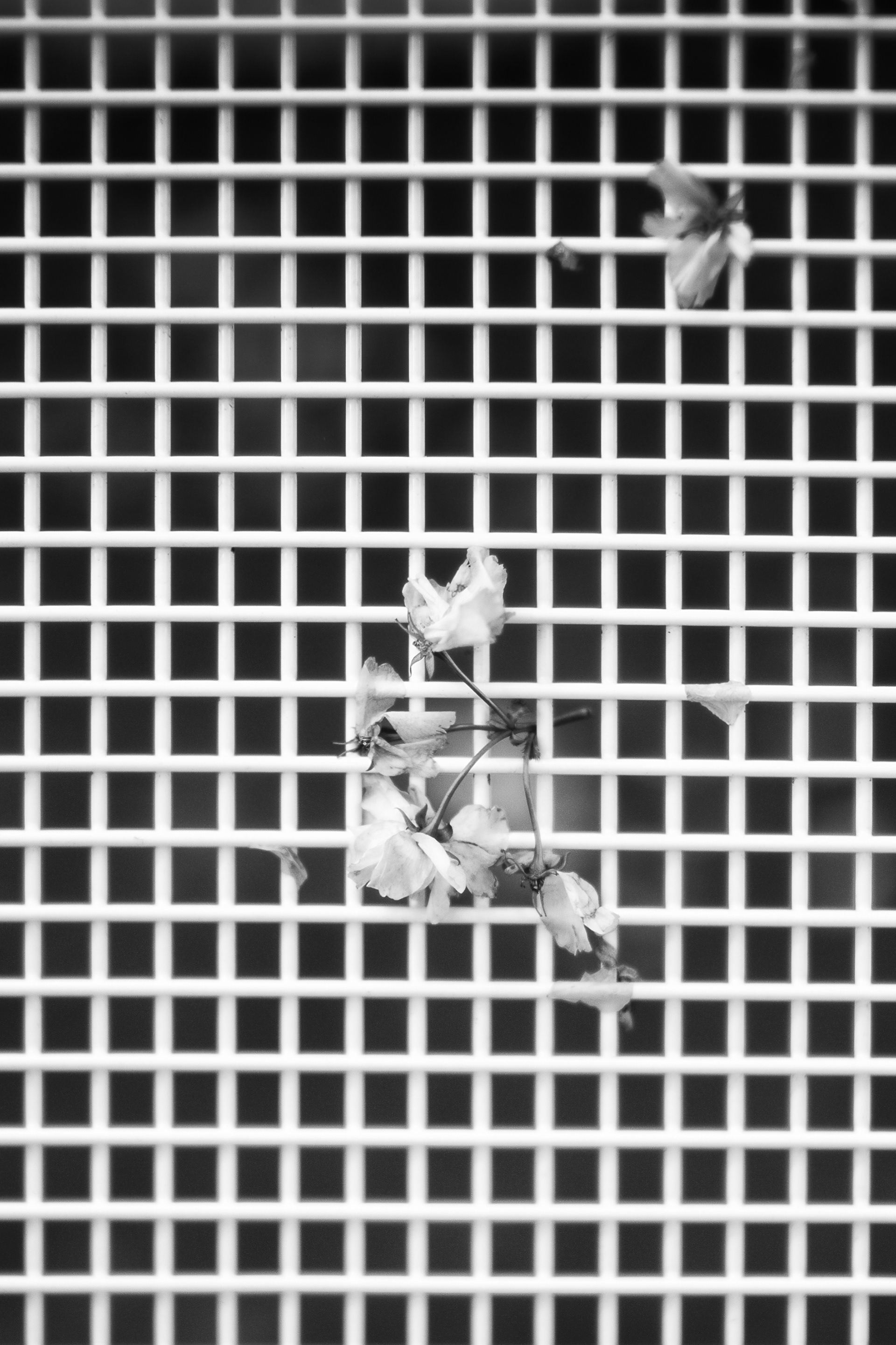

Joseph Beuys was of course that exceptional artist of the twentieth century and whose idea of the flower and of warmth, as for Novalis, was central to his art. The very young artist Nils Dunkel, also from Düsseldorf, at whose famous Academy he is still studying – although he has already had his first public exhibitions there and in Berlin – has the idea of the flower immortal if already perhaps “forever” (“ewig”) wilting in a room that is its own lightened dreamland of the night. Nils seems too, been always fascinated by the idea of the silhouette, that is in itself a major trope of the classic world of Romanticism too little explored – and which in some respects are the origin and even to this day the continuity of photography that has become so central to contemporary image making and therefore art.

When I first came across Nils as an artist I was taken by his elegantly simple recollections of the art of the Hamburg Romantic Philipp Otto Runge himself one of the great masters of the cut out flower silhouette, done when he was very young but whose influence clearly fed into his masterworks “the Times of the Day” where the immortal undying flowers are so essential to that artist’s idea of “ornament”, as they are equally, taking more current forms to Nils. The symbolism of the human drive to ornament is another essential aspect of his art that that legitimises his insistent and geometrical repetition of the flower motif and which for all its minimalist implications hide the ancient traditions implicit his drive to making his own original visions of that beautiful space which they of necessity demand. For of course contemporary technologies in this digital age are implicit always. But then since the beginning art has always stretched towards new techniques, whilst disguising them away as much as possible in order to achieve a sense of timelessness. That sense of “the forever”, never to die or be “out of date” idea needs to remain to the front of the viewers thoughts whilst looking and absorbing all art. That is that “Romantic” drive that needs to remain still part of our present. It enables our young artist to find strategies to open up further lines of enquiry whilst keeping up the essential and necessary simplicity that his way forward on an already clear and visible path seems to beckon.

But a young artist needs to find her / his own personal even subjective radicality within that innate sometimes even subconscious, perhaps little knowing but real sense of cultural tradition. Nils has found his own simple way forward – his usually quite small discrete canvases are not upside down, rather they are reversed so that what is normally invisible and secret when on the wall can reveal a sense of truth – like the “secret” truths behind the paravent that wants to be hidden, but nonetheless provoke that anticipatory excitement which art demands. That excitement meets his innate sense of delicacy and precision – the flowers neither alive or dead but suspended, even when drawn with light and allow us once more to relive relevantly the truths behind the Blue Flower – paradoxically even deprived of its actual physical colour which needs to reside in the viewers imagination. And perhaps the striving towards “noble simplicity” (Winckelmann’s “Edle Einfalt”) is still the best!